Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is highly heritable, and the results of a study led by investigators at the Mass General Brigham suggest that a person’s maternal versus paternal family history of memory impairment/AD could influence their own risk of increased brain levels of amyloid, a biological marker of AD. Evaluating data from 4,400 cognitively unimpaired adults ages 65–85 years, the team found that those with a maternal history of memory impairment at any age of onset, or with a paternal history of early-onset memory impairment, or a history on both parents’ sides, had increased levels of β-amyloid (Aβ) in their brains.

“Our study found if participants had a family history on their mother’s side, a higher amyloid level was observed,” said senior corresponding author Hyun-Sik Yang, MD, a neurologist at Mass General Brigham and behavioral neurologist in the division of cognitive and behavioral neurology at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Yang is also a physician investigator of neurology for the Mass General Research Institute. Reisa Sperling, MD, a neurologist at Mass General Brigham, said the findings could be used soon in clinical translation. “This work indicates that maternal inheritance of Alzheimer’s disease may be an important factor in identifying asymptomatic individuals for ongoing and future prevention trials.”

Senior corresponding author Yang, together with co-author Sperling and colleagues reported on their findings in JAMA Neurology, in a paper titled “Parental History of Memory Impairment and β-Amyloid in Cognitively Unimpaired Older Adults.” In their report the team stated, “Our results suggest preferential maternal inheritance of AD starting from the preclinical stage, a finding which has broad clinical and scientific implications.”

AD is a heritable disease, with heritability estimates ranging between 60% and 80% in twin studies, the authors noted. They further commented on previous studies that have investigated the role that family history plays in Alzheimer’s disease. “A family history of AD can increase the risk of developing AD dementia by approximately 2 to 15 times depending on the number of affected relatives,” they stated. “Further, family history in one or more first-degree relatives can estimate β-amyloid (Aβ) burden in older cognitively unimpaired individuals, suggesting that family history may capture the genetic liability of AD in preclinical stages.”

Some previous research has indicated that maternal history represented a higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s. “Studies have suggested that maternal history of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease, but not paternal, predisposes individuals to higher brain β-amyloid (Aβ) burden, reduced brain metabolism, and lower gray matter volumes,” the team stated.

With access to a larger clinical trial data set, Yang and colleagues wanted to further investigate the question of whether maternal or paternal AD impacted on disease risk among cognitively normal adults, but in a much larger study involving cognitively unimpaired participants. “… earlier studies investigating family history and AD biomarkers had limited sample size and lacked statistical power to fully determine the extent to which maternal history and paternal history affect AD pathology in the preclinical stage,” they noted.

Findings indicate that a person’s maternal versus paternal family history could have a different impact on risk of accumulating amyloid in the brain.

For their reported research the team, including investigators from Vanderbilt and Stanford University, examined the family history of 4413 older adults from the Anti-Amyloid Treatment in Asymptomatic Alzheimer’s (A4) study, a randomized clinical trial aimed at AD prevention, for which Sperling is a principal investigator. Trial participants were asked about memory loss symptom onset of their parents, and also if their parents were ever formally diagnosed or if there was autopsy confirmation of Alzheimer’s disease. “Some people decide not to pursue a formal diagnosis and attribute memory loss to age, so we focused on a memory loss and dementia phenotype,” Yang said.

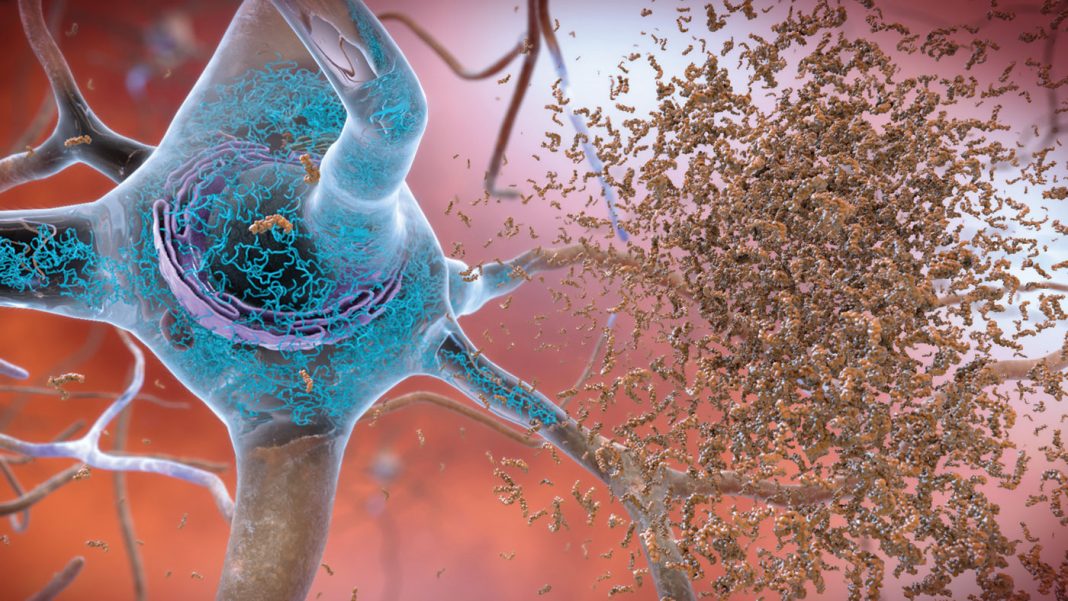

The researchers also used Aβ-positron emission tomography (Aβ-PET) to measure amyloid in the cognitively unimpaired participants. Their combined results indicated that maternal history of memory impairment at all ages, and paternal history of early-onset (age less than 65 years) memory impairment, were associated with higher amyloid levels in the asymptomatic study participants. In contrast, the results indicated, a paternal history of late-onset memory impairment was not associated with higher amyloid levels in the unsymptomatic individuals.

“If your father had early onset symptoms, that is associated with elevated levels in the offspring,” said Mabel Seto, PhD, first author and a postdoctoral research fellow in the department of neurology at the Brigham. “However, it doesn’t matter when your mother started developing symptoms—if she did at all, it’s associated with elevated amyloid.” The authors wrote in summary, “In this study, maternal history of memory impairment at any age at onset was associated with β-amyloid burden among asymptomatic older individuals, whereas only paternal history of early-onset memory impairment was associated with offspring β-amyloid levels.”

Seto works on other projects related to sex differences in neurology. She said the results of the study are fascinating because Alzheimer’s tends to be more prevalent in women. “It’s really interesting from a genetic perspective to see one sex contributing something the other sex isn’t,” Seto said. She also noted the findings were not affected by whether study participants were biologically male or female. “There was no significant interaction between participant sex and maternal history on Aβ, suggesting that both sexes might preferentially inherit AD risk from mothers,” the authors commented.

Yang noted one limitation of the study is some participants’ parents died young, before they could potentially develop symptoms of cognitive impairment. He said social factors like access to resources and education may have also played a role in when someone acknowledged cognitive impairment and if they were ever formally diagnosed.

“It’s also important to note a majority of these participants are non-Hispanic white,” Seto added. “We might not see the same effect in other races and ethnicities.” Seto noted that the next steps will be to expand the study to look at other groups and examine how parental history affects cognitive decline and amyloid accumulation over time, and why DNA from the mother plays a role. “Future studies with longitudinal data will be necessary for a fuller understanding of the potential role of parental history of dementia in offspring AD risk,” the investigators stated.